What's acceptable once you've been accepted? How far will you go to create something different, to defy other people's expectations? In the last post, we discussed Pollock's later work and how it disappointed his main man Clem Greenberg. Clem said that Jackson had lost his stuff, and this judgment became dogma. In another instance, Picasso had his later works written off. Most of the Art World cognoscenti hated these late paintings and made pithy comments like this one from Douglas Cooper, "incoherent scrawls done by a frantic old man in death's antechamber." De Kooning's late work is often described as being made by an increasingly senile old codger who sat drooling in the corner of the studio while assistants polished his last dribbles. Rothko's later black works were made by a deeply disturbed man heading toward suicide. Guston's last figurative phase was a lousy calculation by a mediocre abstract artist.

So were all these naturally curious and defiant avant-garde artists just supposed to sit there pontificating about this or that past innovation until they went tets up? Were they supposed to fiddle with the corners until the Reaper came calling? These were bright, imaginative, and masterful artists. They may still have new and different things to say about their contributions. Perhaps life took them into a dark room and kicked the crap out of them. Maybe they were sensitive enough and connected to the world around them enough to see where they might still contribute. These artists found new inspiration and pushed for as long as they could. Fuck the haters!

Brice

Brice Marden arrived in the middle of Sixties Minimalism with a different idea about painting. He wanted to define this stripped-down machined aesthetic with older virtues - personal narratives, human interactions, and hand-made fleshy physicalities. Brice's inclination to Romanticism may have seemed out of step and contrary to those busily producing manufactured objects. But when painters saw his work, they found his humanism convincing. Something extraordinary was going on here.

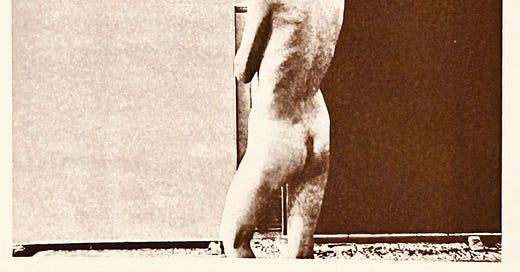

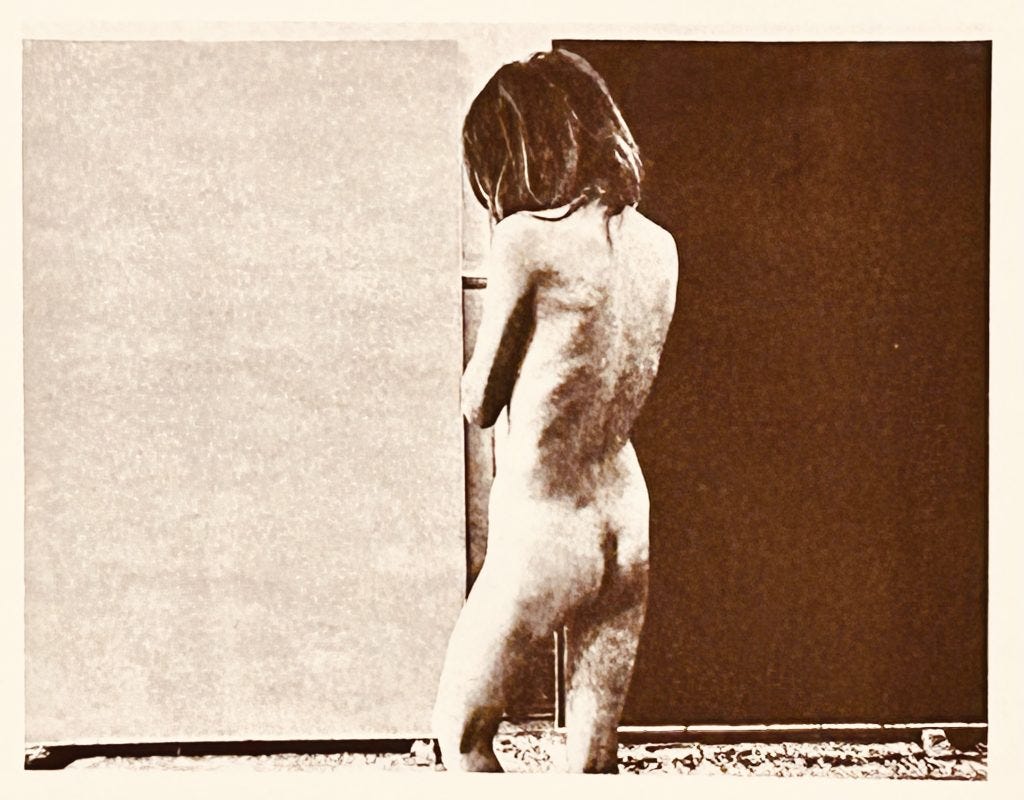

Marden's sources for his paintings are legendary. He respected and had actually worked for Rauschenberg. He was enamored with Johns. There are also elements of John Cage's philosophies in his work. You can see Bob's White Paintings and Jasper's Targets come together. Brice filled the geometric support structures with an idiosyncratic monochromatic palette and a smooth, leathery surface. No images intruded on the canvases. It was immaculate. Marden focused and connected this work almost exclusively to personal subjects and lived experiences. It surprised people. One series of paintings, subtitled "Back," is related to a rough period in his marriage.

Marden's reputation grew among artists. When the 70s arrived, painters found themselves left out of the avant-garde - painted into a corner, you might say. Marden was also restless, so he began to experiment. His first solution was practical. He retained the monochrome canvases and began to combine them, creating straightforward geometric compositions - diptychs and triptychs. These compositions allowed for more complexity and interplay, mainly with color. However, these works do not speak of a drastic change, nor do they challenge or greatly expand his visual ideas. Instead, Marden's visual restlessness took shape in his drawings and journals. Brice was creating something unexpected - sloppy, loose, and poetic. Something was changing his mind.

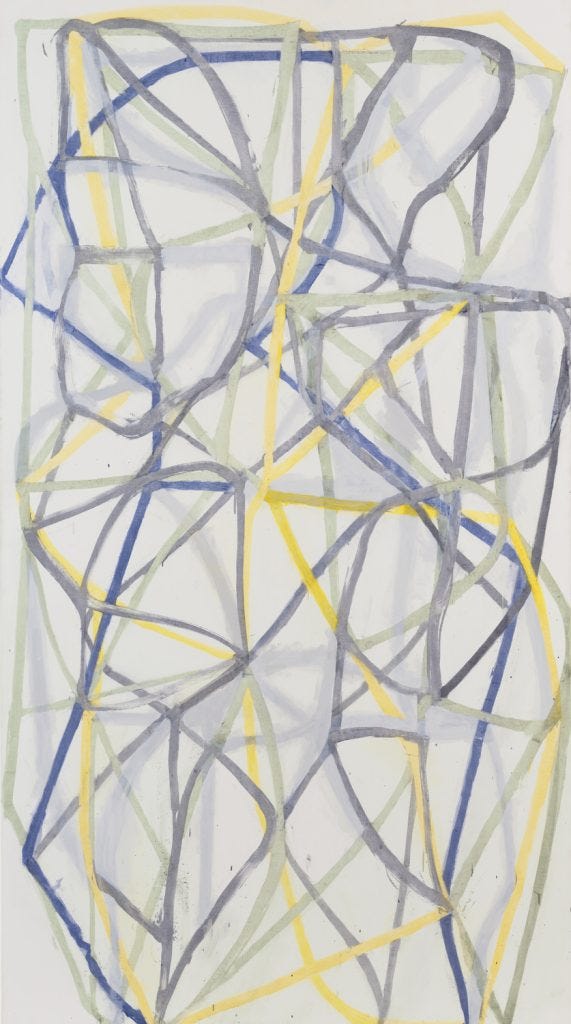

Then, in the mid-1980s, Marden made a shortlived and tentative series of grids with palette knife smears on monochrome grounds. These works are uncertain but compelling. A couple of years later, he let loose with brush strokes that were quick and performative on a spare and worked ground. We all took a deep breath… something unexpected was happening here. Instead of the building up of the surfaces, the surety of the geometric support, and the beauty of the fetish finish, we got scraped grounds, overpainted erasures, and a resurgence of painted abstract imagery.

The bad news was that these paintings were instantly marketed. There was a push to connect these marks to calligraphy. There was also a lot of rhetoric about Eastern mysticism and New Age spirituality. Woof! I get really itchy hearing this kind of talk. I'm all in for a discussion of Romantic sensibilities and source materials. Still, I will check out the bar around the corner when someone starts getting watery-eyed about their spacey superpowers. So, from here on, I will misunderstand these works to suit myself. If you want to have a read about these things - Google awaits. I wanted then, and I want now, desperately, to like these paintings without that kind of horseshit.

First and foremost is how restrained these lines are. You can easily trace Marden's careful movements around the canvas. The colors are polite and deliberate. There isn't a hint of expressionistic exuberance in Couplet IV above. Instead, what we get is a steady discovery. You're following his hand, watching it move. Color over color, tracing the top and sides of the canvas and then falling off at the bottom. Instead of burnishing the color out to the edges as he did in the 60s and 70s, he's defining those sides with pathways and gestures. The brush sometimes gets lost in the fog of memory within the ground or gets scraped away to make room for new memories. Brice reconsiders the path as he traverses it. He's showing control in the face of the unknown. And I like this idea of painting - very much.

All through these forays and reconsiderations, Brice's emotional range stays easy, steady, and slightly un-grounded. It's like he's whispering to us, searching for the right words after a long drag - holding his breath - then slowly exhaling into the moment. After a few trips through this particular Couplet, I'm wasted, dazed, and confused. I know Brice has said something profound about what's just happened, but I don't know, at least not yet, what that might be…. Ambiguity. You know?

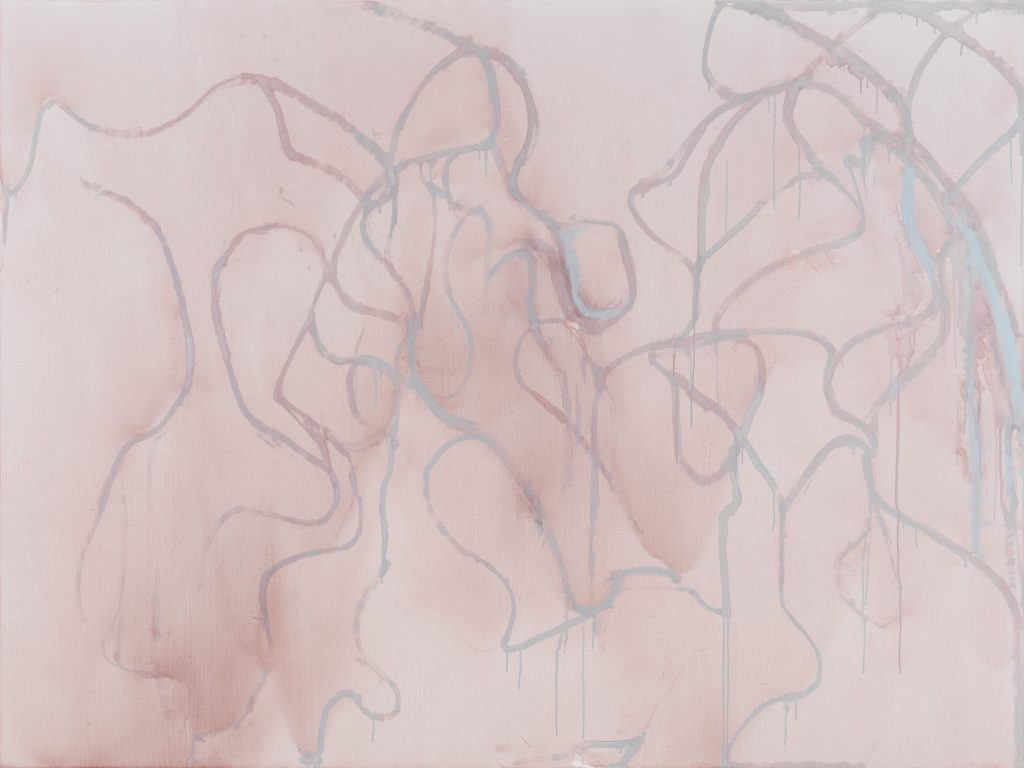

Brice followed the paths on those surfaces until the end when he somehow brought the surfaces and the structures together. The show "Let the painting make you" at Gagosian in 2023 says it all for me. I still have that pink painting Lingerie in my head, and it has stayed with me like a bittersweet memory after a long goodbye. The simplicity of the image and line pulls us onto the ground. The way the image breathes is surprising. You can almost feel the pulse in it. Brice lightly covers the structural bones like a thread-bare linen sheet draped over a lounging lover. Slow, soft, easy, familiar - you follow some of the pathways out of the edges and lose others in the haze. Until finally, it's gone, and you catch the scent of perfume in an empty room. Perfect.

"And to me a painting isn’t just some facts. A painting is more like, you know, it’s a lot of things, but it’s frozen for study and for feeling. I mean if there’s any working method, it’s just keeping it open so you can put in as much as you want to put in, or try to get it in, having it be an open-ended situation rather than a closed situation—in opposition to Formalism....

I think of my paintings as icons—but the icon is really open to all sorts of interpretations. It doesn’t just become some physical fact that you can’t read beyond. There are 14 icons that can’t be traced to human hands, acheiropoetos, meaning not made with the hand. Icons made by something other than human hands. I mean, that’s to me the kind of painting you strive for." [Saul Ostrow in Conversation with Brice Marden]

Frank

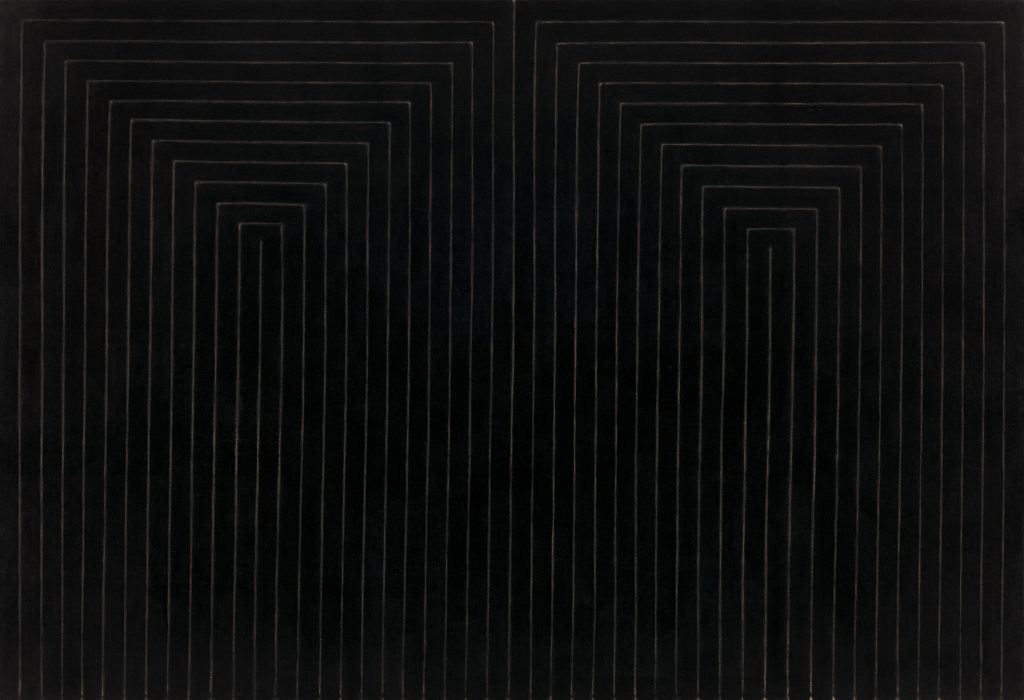

We all know Frank's work - but if you don't, get on it, dopey. In 1959 Stella kicked open the door. He absolutely reduced AbEx painting into surface and side, process and material, creating immediate and comprehensive abstract images. Frank was an enfant terrible, an iconoclast, Dalton at the Road House… er, Cedar Tavern. By lesser hands, this kind of work would have been merely logo painting. But Frank makes these paintings historically inevitable, unavoidable. He took this line of thought and imagery through the 1960s - one masterwork after another. His visual logic and pathways to imagery are astounding. It's the kind of groundbreaking feat few artists in history have managed.

But when that run during the '60s ended, Frank began getting new ideas about painting. So, Stella decided to rock the boat again by looking at a broader history of abstraction. He wanted to make more expansive, abstract, and Modern work. European painting invaded his consciousness and took up space. Frank opened himself up to the world around him and began to see new open spaces for painting everywhere. And in no time at all, he had turned his successes upside down. It was difficult for many folks to see, let alone understand. Many thought Frank led them on. But Frank was fearless - he didn't prepare anyone for it. Stella didn't retreat. He went all in. Outcomes be damned. It was glorious!

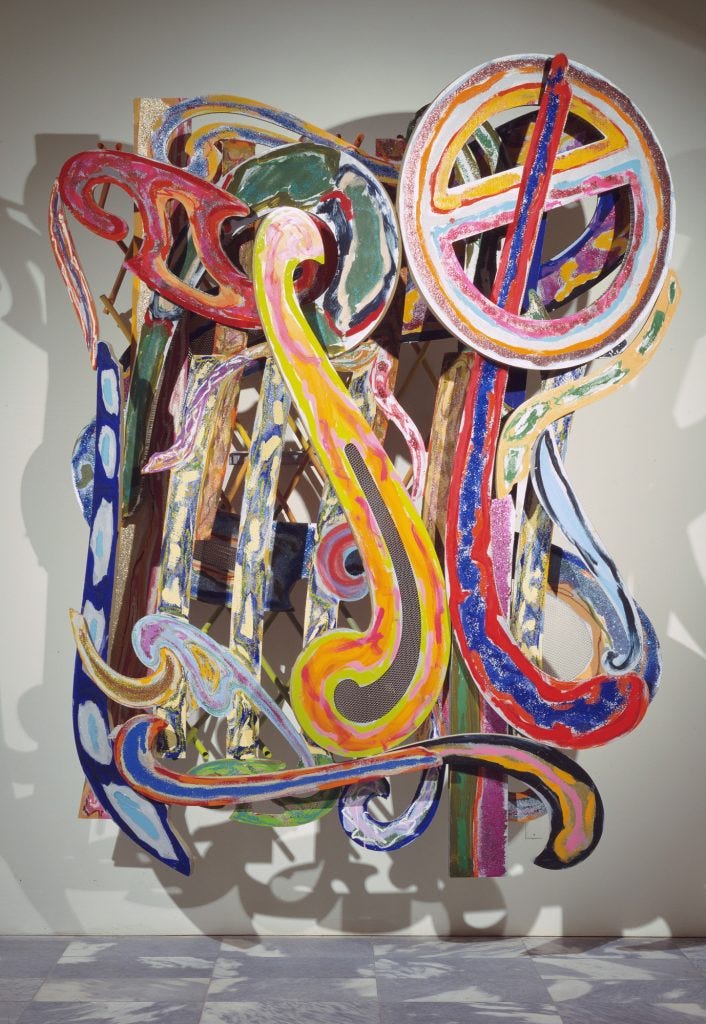

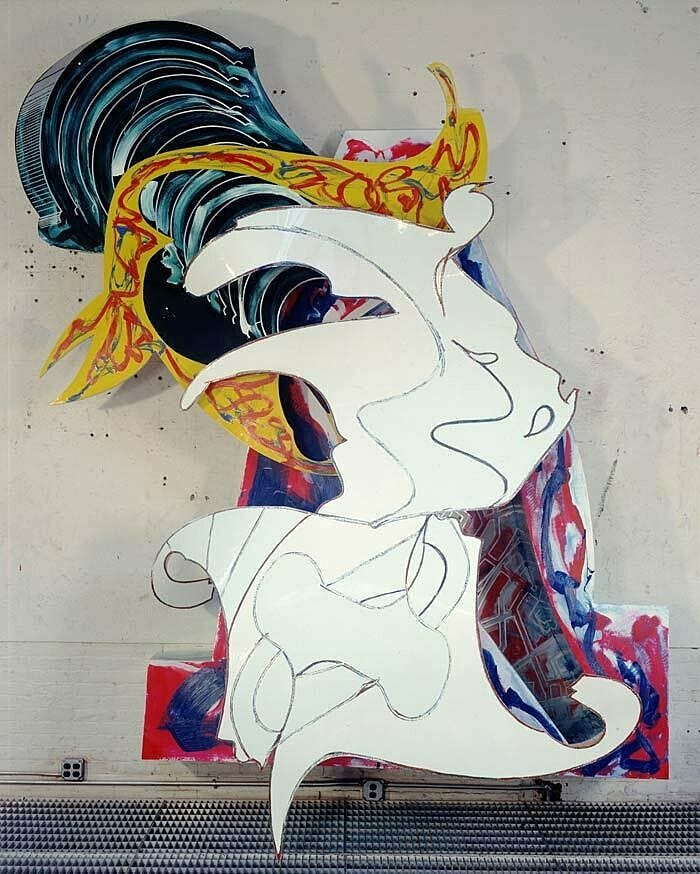

These new works moved off the wall and created their own spaces. Frank overcame the idea of illusion by removing it from the equation. He actually built space right into the work. This allowed his abstract imagery to exist in our physical world - like sculpture. He reinterprets Rauschenberg's combines, "…a body of work… consisting of three-dimensional objects integrated into paintings." Stella instead turned the painting itself into a Three-Dimensional Object. He used the paint in decorative or festive ways, wrapping the geometric imagery in Matisse's florid fabrics and Picasso's sexy primitivism. These inspiring works look like they were made to honor the primitive gods at some holy festival. Again, the “religion” implied in that idea makes me nervous, but Frank is firmly in this world, not the next. This isn't about reviving spiritual issues; instead, it's about confrontation with pictorial ones. Throughout the 70s, these things began to form into monster sizes, and Frank kept building them out. By the 80s, these giants were redefining our expectations of abstraction itself.

But for me - I still wanted the fucking painting, the traditional structure, the canvas, the paint, the imagery, the illusions, the falsity of it all. I wanted Rubens or Caravaggio to tell me a lie that's actually the truth. When Frank's Wall Monsters work, there's nothing better. They're like Transformers morphing out of 18 Wheelers, becoming Bad-Ass Kung Fu Robots. But I still wanted the canvas. I wanted the traditional support. There were hints, all along, that "traditional painting on canvas" could happen for Frank. There were the prints, of course. Then, that explosion of a show at Gagosian on Wooster Street in 1995. Wow! And a few years later - it happened…

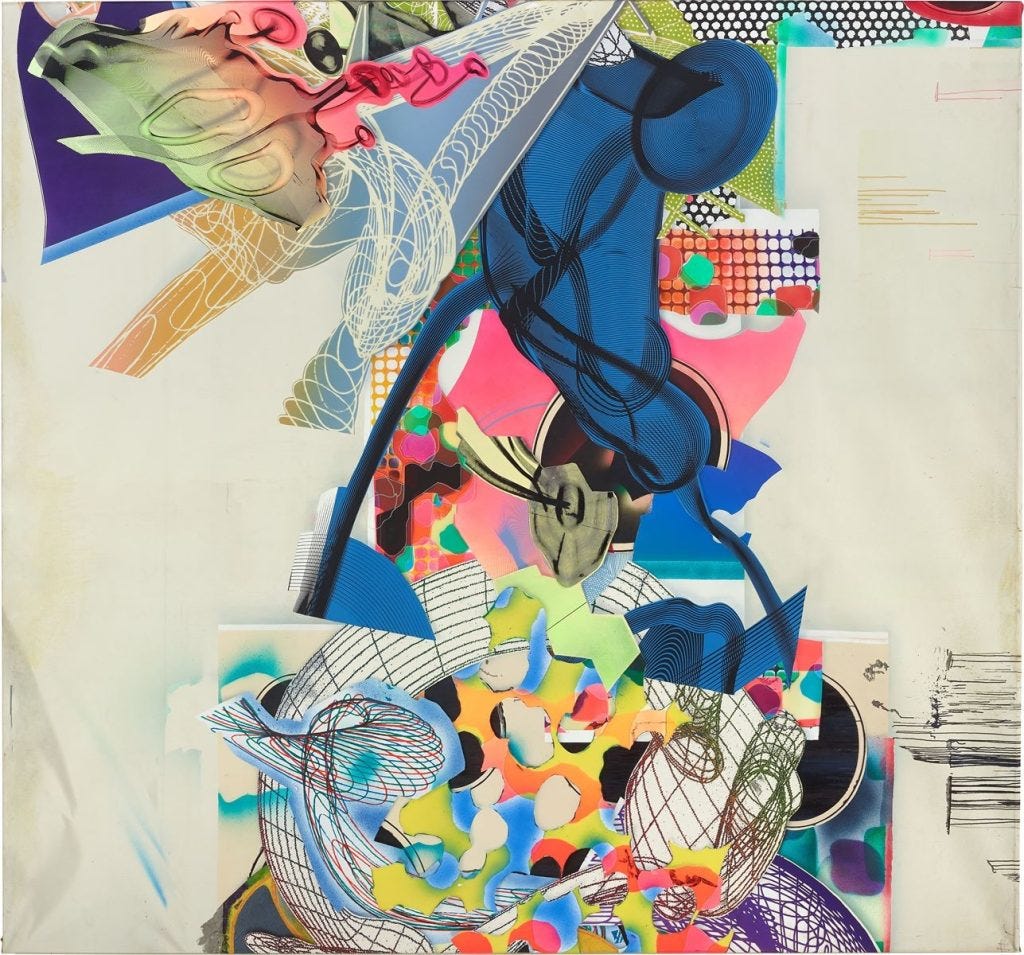

One of my most memorable experiences with Stella's abstract painting was in Paul Kasmin's Garage in Chelsea shortly after 9/11. It seemed strange that a show would open at that time. I mean, who should care about art when the air in NYC still holds the smell of fire? But everything at that moment in time was strange. And I mean everything. So, I embraced the strangeness, hopped on a subway car, and walked into Paul Kasmin's garage on 26th Street in about an hour.

Frank was not holding back. Not at all. I saw some raw-looking, back alley abstract images "painted" on worked canvases. These paintings were set on taking us all into a new and violent 21st Century. How did Frank know? How could he know? None of us did. It's no wonder that no one wanted to see this show for what it was. Many artists I knew then did not go to the show, or if they did go, they parroted the critiques below. There was not much praise - just more of the same familiar criticism saying that a once great artist had lost his stuff. No one seemed willing to acknowledge that Frank was tearing a giant hole in the abstract painting universe. Again, for Chrissakes!

"I nonetheless urge everyone with an interest in the fate of abstract art to see it, for this may be the single most appalling exhibition of a famous abstractionist you are ever likely to encounter. It is guaranteed to make you shudder, and not with pleasure, either." [Hilton Kramer on Frank Stella 2002] Fuck off, Kramer.

I have kept this show with me ever since. I remember practically everything about it - the strange lighting, the smell of garage dirt, the unrestrained ambition, and fearless experimentation. I loved the raw, dirty ground left aside in these paintings. I liked the sagging bits on the stretchers. I was thrilled with how the abstract images crashed across those ratty surfaces. It was truly startling. And it left me with the overwhelming feeling of seeing something I wasn't supposed to see, like accidentally walking in on one's vigorously rutting parents. That sort of thing changes you - you know?

Stella was approaching abstract imagery, as he said, through Working Space. He wanted an expansion of the visual field to allow for new possibilities of movement and form. He wanted abstraction to mutate, to overwhelm that expanded field and push beyond the edges into our space. While this clear description works in print - it doesn't carry any of the ferocity or the rudeness of the things I saw in Kasmin's Garage! Stella's trenchant ideas about Working Space were radically redefining how abstraction could work right before my eyes. This show broke the doctrinaire cultured abstraction that was being shown in the studios and galleries at the time, making it look inert and irrelevant. In Frank's show, you actually tasted the grease and iron. You could feel the rusted parts and the rough soldered joints Stella had used to reconfigure the engine of abstraction. And when you turned the key - these things roared to life. Working Space really does work! It just isn't very pretty. It doesn't have to be.

"Rubens certainly was in touch with the Mannerist sensibility of Italian painting before he came to Italy, and this familiarity may have helped him to absorb it and to build on it as well as he did. He brought a sense of motion to what he saw that has propelled painting ever since. The sense of painting that we have today is formed by the space that Caravaggio created being set in motion by the force that Rubens supplied. It is important to see Caravaggio and Rubens in this way because it tells us how we think about painting, especially how we think about why things seem right in painting and about why we think certain paintings are great.

To put it simply, our notion of what aesthetically proper visual organization of painting should look like is based on the notion of a perspectival box, a container for measurable space. This container is basically a free-floating cube, although our senses will tolerate a sphere. Painting has to be organized in such a way that it remains poised within the limits of these notions; otherwise we tend not to like it. This explains why Giotto and Botticelli do not satisfy us. The justification for the aesthetic harmony that we experience in the face of Giotto’s flatness and Botticelli’s stiffness is unconvincing, and it will always remain that way. Although we acknowledge that these two painters have made great art, we will never see their deployment of pictorial space as resolved. They will always belong to a tolerant notion of art that accommodates the activity of painting before it became the activity we know today — the activity of making coherent pictorial objects, pictures that do not conflict with our present notion of visual focus and organization." [Frank Stella in "Working Space" - pg 64]

The Whitney Retrospective was one of the best shows of the last decade. The sweep of Frank's career was revelatory. One hit after another, one great visual idea leading into the next. All abstract. All the time. 24-7-365. I was especially taken by the White Whale Wall. The inches of Working Space in those "paintings" took us miles away from the tastefully restrained boardroom backdrops in the Whitney collection. But the kicker for me was the large collage painting at the entrance - Das Erdbeben In Chili. Abstraction for the 21st Century is all over that work. If you're a painter who had walked out of that show unchanged, there's something wrong with you. Take that mid-career!

"... But people want to make art into something else—or more. Painting is very rich and for me it better be a satisfying and rich experience. I don’t like a lot of the stuff that goes on in the art world, but it’s hard to be old and like what goes on around you. Anyway, the real point is that the things that don’t seem to me to be pictorially informed are not so interesting to me. I can’t help it....

Yeah, I think it’s true. The most important thing is that you deal with it pictorially, you worry about making pictures.When it’s successful the result creates a visual experience, but it does something more. It makes available to you both a kind of experience and information that you couldn’t have gotten any other way. If the artist hadn’t made the effort to express what was there in pictorial terms, it would have been a different kind of information, if it would be anything. The pictures are special in that way and they add something to the world. They add something to the sum of knowledge. You don’t get it by being an artist. You get it by worrying about what’s pictorial." [Frank Stella in conversation with Saul Ostrow]

Marden & Stella. It's always interesting to find different viable solutions to the same problem. But the problem has to be clearly stated. So I ask you - is there something about painting that needs to be solved today?