A couple of experiences changed my mind this year. The first involved a double encounter with Christopher Wool’s work – one overlapping with the other.

At the beginning of the Summer, I went downtown to a wonderfully fucked-up space in the financial district to see a show of work that included “paintings,” “sculptures,” “photographs,” and a mosaic. Wool's works were presented in a demolished office space. The raw rooms were unique in a building filled with dreadful tech-upgraded offices. You know what I’m talking about – contemporary conveniences and technological upgrades that tend to overwhelm antique early modern architecture. So when the elevator doors slid open, it was a bit of a shock to be confronted with an “office space” ruin. Who knew a Victorian folly could manifest here in the 21st-century financial district?

All through the exhibition's run - everyone who reviewed it and the artists heard talking about it - were throwing about the term "context" while waxing rhapsodic about how delicious the exhibition looked. However, trying to find what this "context" was exactly, how this "context" was supposed to help define the work, and why this "context" should matter in understanding the work was never clearly defined by anyone. This "context" was like a recipe everyone "knows," but no one could agree on what ingredients should be used.

Dave Hickey understood the appeal of Christopher Wool's work but was not a big supporter of it. He said something about Wool's retrospective that still rings true. "The problem of location is particularly daunting. Museum exhibitions, after all, must take place in museums, and unfortunately, the heartless, colorless conceptual ambiance of the contemporary kunsthalle is precisely the “look” that Christopher Wool is marketing to private collectors in whose homes his simulacra of downtown, not-for-profit virtue look tough and elegant. They allow private citizens a little touch of Dia in the living room and the paintings truly thrive in these secular contexts. Actually, hanging a painting by Christopher Wool in a museum, however, is like reprinting one of Andy’s Marilyns in Photoplay. It seems at once redundant and oddly dissonant—like the weird tang of a chicken omelet—the kunsthalle being the chicken, in this case, and Wool’s painting the egg." Chicken Omelet! Holy fuck. [Dave Hickey on Christopher Wool's Retrospective in LA.]

And Dave's trenchant criticism may have impacted Wool's thinking. "…the whole point of the installation is create an environment where the work can play off the architecture in ways that can't be done in a traditional gallery or museum…. i’m sure this will have the potential to open other ideas… but there is no reason for me to think that this negates exhibiting in more traditional spaces… including the 2 paintings from the 90’s is a chance to see works that may have been exhibited in more traditional spaces in this alternative environment and i think its interesting to see how much the environment impacts how works are perceived…. maybe it's another example of the failures of the modernist ideal…." [Christopher Wool in an email conversation with Brian Boucher]

If you read the whole email "convo" between Wool and Boucher, you'll see that there's enough "nudging" and "winking" going on to make one believe that maybe, just maybe, there's something real there. I particularly loved this - "...almost everything in the exhibition has a link of some kind to something else in the exhibition….and the take away should be that so many of these different works are sourced in similar ways…making a large mosaic employs very similar means to what i do with silk screen or metal casting in painting and sculptures….this reuse across mediums creates new generations of images…." At this point in abstraction's history, who among us doesn't love the idea of the failures of the Modernist Ideal, right? But I fear this conversation is more of a Python-in-a-Bar kind of thing.

"A nod's as good as a wink to a blind bat! Say no more!"

The second Wool encounter was at a new office building lobby in Hudson Yards. The building owners were presenting Wool's enormous commissioned mosaic entitled "Crosstown Traffic." Wool must have had the annual budget of a small country at his disposal to realize this thing. And it shows! The production is astonishing. The image is classic CW Brand Inc. - overworked blobs, mushy print stains and sticky lines. But this isn't your usual lobby billboard. The image has been upgraded and customized into a luxury art experience that sparkles and glints as you move around the lobby. There's nothing rude or untoward about the imagery or the abstraction. I mean - no one's gonna piss in your fireplace during your reveal party. The mosaic itself is static, but very expensive looking. It's not just devoid of emotional content; it's positively blank. But strangely, the thing has a presence because it's encased in a beautiful wall of Scadinavian-inspired wood paneling. This mosaic is sexy in the same way that a shirtless Ryan Gosling in a preposterously ugly and expensive fur coat is sexy. You know - ridiculous, camp, and way over the top.

“About the Artwork – Whether via painting, drawing, sculpture or photography, Christopher Wool’s artistic practice often involves the translation of images from one medium to another. It is through this process of translation that Wool’s work takes on extraordinary complexity and depth, and confronts the core qualities of art.” [Brookfield Properties Press Release]

Upon reading the PR from the real estate folks, we should also ponder some other unanswered questions. They've given us no hint or explanation of what the "core qualities of art" might be, which is typical nowadays. What does "translate an image from one medium to another" mean? What happens to the image in that process? Do the "core qualities" change, and if they do, then does this change the meaning of the image? Or is it all "just cool" - full stop? Can a perfect replica of The Abduction of a Sabine Woman by Giambologna made with candle wax manufactured by Urs Fischer rely on the same meaning as the original The Abduction of a Sabine Woman by Giambologna? Why a candle? And what happens to the piece if that expensively produced candle melts? Is the flame a Duchampian moment similar to the solution of the broken glass (an accident), or is the "accident" in the candle built into the piece (in other words, not an accident)? Oh my, oh my! The questions go without answer!

In both of my encounters with Wool - the rough hewn space in the Financial District folly and the arena lobby space in the techno-shimmering Hudson Square - I had no memory of a specific image. No encounter with a unique meaning within the particular works themselves. The work in itself is not meant as a singular encounter. Instead, I was supposed to remember the experience of the exhibition and the presentation of the works. Even though this was impressive, I think Hickey's critique is still relevant. Wool's work emerges from the "...heartless, colorless conceptual ambiance of the contemporary kunsthalle...." Is that still "just cool"?

Ok, take a breath. Truthfully, I am seduced by the downtown ruin (ah, the nostalgia of it all - we were all so young and full of ourselves. Piss & Vinegar, Baby!) And Wool's show had a kick to it. But, nostalgia is everywhere in the 21st Century. We've built the entire culture on it. Ridiculous!

As for the other installation I am absolutely repelled by that midtown corporate talisman. Downtown Wool's show is a beautiful lie about a lost era draped in appropriated decadence. It's a halcyon experience. The Midtown abstraction is fucking Lenin's tomb - a frozen corpse from a bygone era served up in a glass vitrine.

Same work.

Same ideas.

Different places.

I fear I know that I've experienced this many times before...

And you may ask yourself, “How do I work this?”

And you may ask yourself, “Where is that large automobile?”

And you may tell yourself, “This is not my beautiful house”

And you may tell yourself, “This is not my beautiful wife”

My first visit to Pollock's home and studio in the Hamptons was the other thing that rocked me. That old shed out back was absolutely marvelous. After Pollock's cousin gave an outstanding presentation, we entered the studio. The shed had the feel of a hothouse that was growing strange things in a dank atmosphere. It was magical. After the tourist experience of walking about the studio in foam slippers, I went out into the yard for a longer look at this place. A stunning sweep of land goes across the marsh to the inlet. There was a glassy slab of blue sky overhead. The summer light seared into the edges of things, which put every inch of the place in high focus and crystal clear. Rich and varied greens blanketed the landscape. It was all so lush and alive!

This landscape gave me a different appreciation of Pollock's work, especially the works that we all know and love. This untamed place took the school, the museum, and the gallery right out of my understanding of Pollock's work.

It's common knowledge that when Pollock made the landscapes, he was "sort of" clean. He was also free. Free of the NY competitive art world. Free of his inner demons. He was safe and cared for. He had overcome the heavy drinking (though he still imbibed) and became enamored with this place. But this Eden was short-lived. Krasner could not protect and care for him forever. She wanted her freedom. She, too, was inspired.

Pollock's success and growing popularity as a "possibly" great artist brought his shadow back. When he realized he was no longer free, he left the abstract landscapes behind and began painting the demons in the room. These last/late paintings are the work that Clem did not like - when Pollock "lost his stuff." But I can't see it that way. I haven't for quite a while now. For the rest of the Summer, I was obsessed with the experience of Pollock's & Krasner's place and Jack's late work. Pollock's "losing his stuff" haunted me.

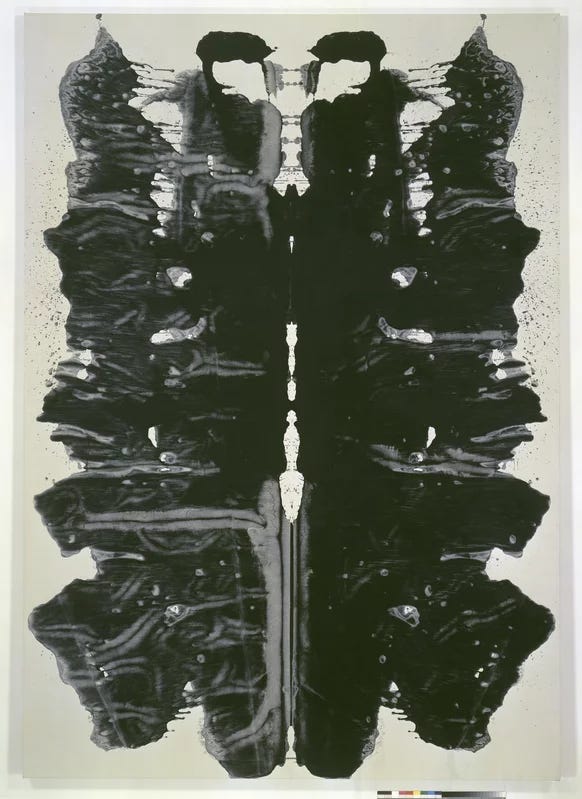

Jack had no choice but to look inward. Confrontation. Realization. His fight with alcohol. His disgust at being a drunk. His loneliness. He carried a deep seated, unending need for comfort. How long those days in the studio must have seemed, especially as every drip and splash revealed another horrific image. Not since Goya's late black works has there been a more dark expression of an artist's life. After this fall from grace became unstoppable, Pollock had only a few seasons left. His ending was inevitable. He would disappear into the bottle. He fell Sideways. And all through this time the demons taunted him in the mirror. Desperate envy. The mania to prove himself. He feared his lack of worth and talent. And finally, he found himself in an endless experience of absolute emptiness. That beautiful landscape Out East could not stop any of this inevitable despair. And Jackson slipped into the deep.

I realized something as I stood in Jack's backyard, having my good vibing "feels" looking at the landscape. Those last works are about a different kind of Context, not the context of "where," an outer Place, but the context of “who,” an inner vision. Pollock looked into himself. His Modernist failure happened because he found the outer world too thin. When life becomes a confrontation with oneself, when one must push into quotidian consciousness, art, necessarily, becomes something more than just a "problem-solving experience. This kind of context, for great artists, creates a brutal and violent type of vision. In these "late" works Pollock painted his existential world - his human "problem." He wasn't worried about Crosstown Traffic. He was opening up his life in the world - at any cost, at all costs.

As I thought about these things, it also occurred to me that his old friend, Guston, would later confront many of these same issues with abstraction. Philip would also discuss the failure of Modernism. (Wouldn't that be a show - Pollock & Guston The Late Works?) - “There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art. That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, and therefore we habitually define its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is ‘impure’. It is adjustment of ‘impurities’ which forces painting’s continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden.”

Pollock's last few years were nothing if not impure. So many self portraits, flayed figures, horrific females, staring eyes, mythic beasts - they all appear in his splashes and drips. These fearful images push you away. They close you in and hold you down. There's none of his landscape painting's openness. There's none of that light or life. There's only Pollock. Bleary-eyed. Drunk. Sybaritic. Angry. Afraid. Everywhere all at once. It's all fucking personal.

"I'm not a phony. You're a phony."

“Our intellectual life is out of kilter. Epistemology, the social sciences, the sciences of texts – all have their privileged vantage point, provided that they remain separate. If the creatures we are pursuing cross all three spaces, we are no longer understood. Offer the established disciplines some fine socio-technological network, some lovely translations, and the first group will extract our concepts and pull out all the roots that might connect them to society or to rhetoric; the second group will erase the social and political dimensions, and purify our network of any object; the third group, finally, will retain our discourse and rhetoric but purge our work of any undue adherence to reality – horresco referens – or to power plays.” Bruno Latour We Have Never Been Modern.

Pollock's late paintings were not made for America's Corporate World. These are not the CIA-friendly paintings that show the rest of the world what great guys we are. They're bleak. Harsh. They show us what a barbarian culture produces in the Modern World. Oh, and by the way, these paintings are not Modern either! The paintings fail spectacularly if you look at them with Modernist eyes. They are "primitive," "mythical," and bloody violent. And no matter where you place these Black and Whites in the world - the museum, the gallery, a ruined office, a corporate lobby - you'll always get the same - vicious - story. Someone will piss in your fireplace. No wonder Clem was so upset. His career was all about promoting beauty, simplicity, and visual calm. But at the end, Pollock extended his middle finger and aimed it right at Clem, grousing about him "losing his stuff."

Fade to black…

It's been a rough year.

And I'll let Mr. de Kooning have the last word to end this strange journey through my head.

“Every so often, a painter has to destroy painting. Cézanne did it, Picasso did it with Cubism. Then Pollock did it. He busted our idea of a picture all to hell. Then there could be new paintings again.” - Thanks, Bill.

So how did any of these ecounters with Pollock and Wool change my mind? Well. I had come to the point where I was absolutely sure that I'd never write another fucking thing. It seems I was mistaken. My apologies.

Mark Stone - Henri - Art Mag